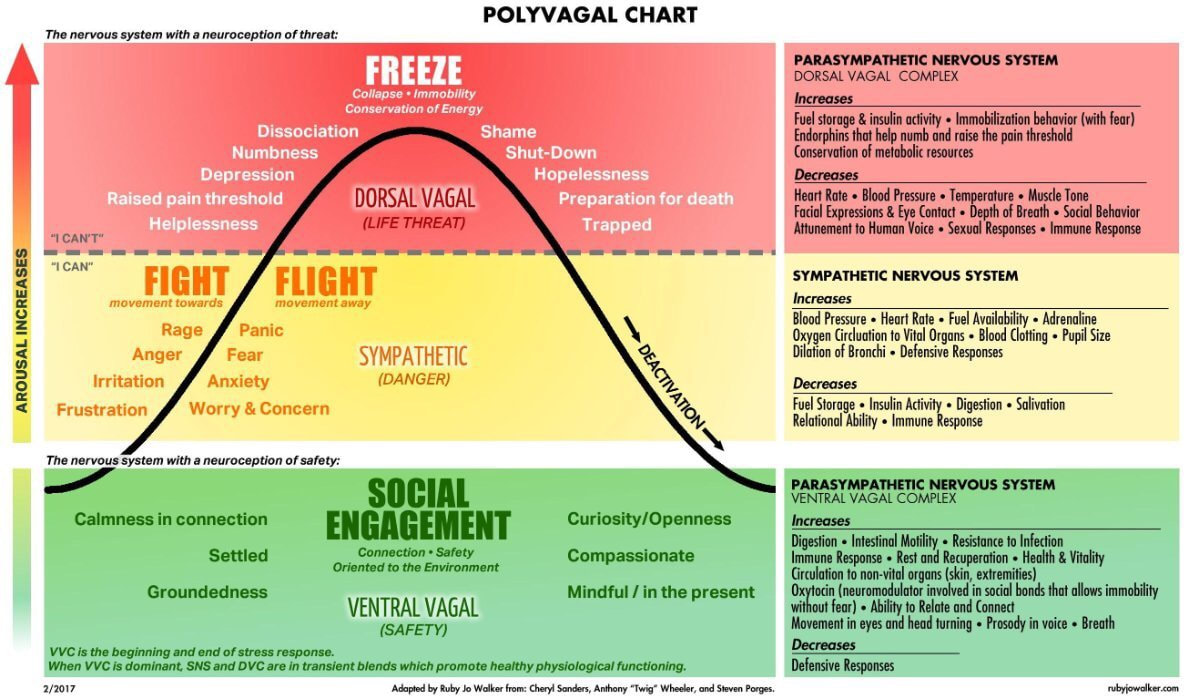

What is the Polyvagal Theory?Stephen Porges developed the polyvagal theory, which explains our nervous system’s response to stress or danger. Once we understand those three parts, we can see why and how we react to high amounts of stress.

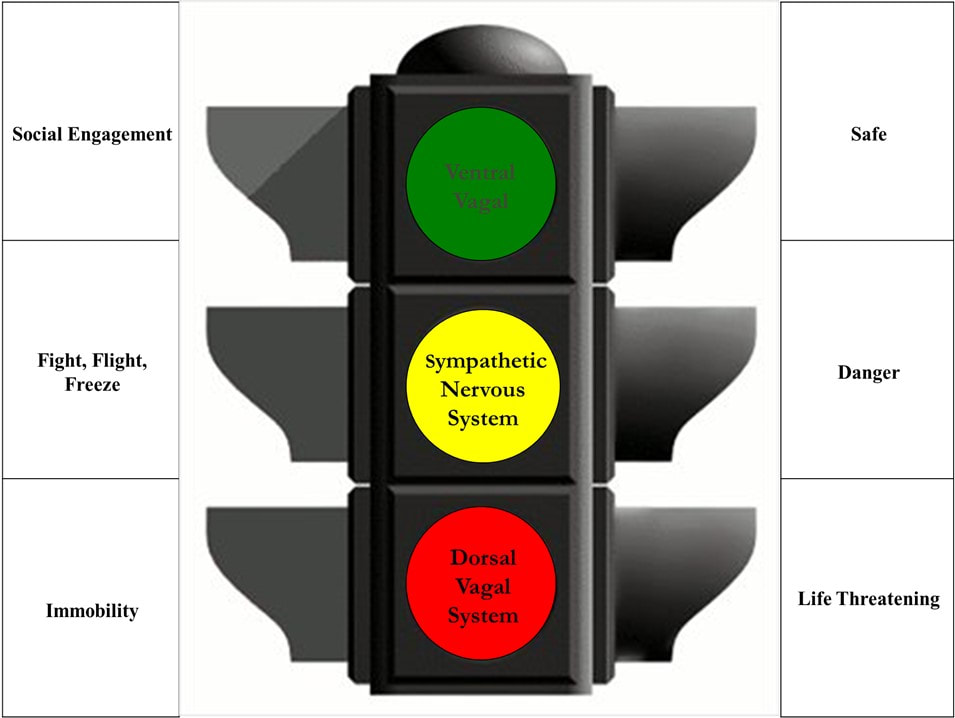

It describes a three part hierarchical system. The first, the ventral vagal is described as a safety system or green zone. The second is activation. This is the sympathetic nervous system getting us ready for fight or flight imaged as the yellow zone. The third system is the dorsal vagal, which is immobilization or freeze imagined as an immobilized red zone. The theory describes how we assess stress or danger based on cues in the environment. If we begin to sense stress, our sympathetic or activation system begins to kick in. Then we attempt to engage our ventral vagal or social engagement system (the green zone). If that doesn’t work, the threat persists or intensifies we employ our activation system. We get ready to take action. Our heart rate increases to prepare us for fight or flight. Then if the threat is too large or we can’t escape the system of last resort, the dorsal vagal takes over. |

A Story About a GazelleAnimals are a great example of how we handle stress, because they react primally, without awareness. The animals do what we would do, if we were not well tamed.

If you have ever watched the video of the cheetah, gazelle and hyena, you’ve seen the cheetah chasing a gazelle. The gazelle runs as fast as it can (sympathetic nervous system), until it is caught. When it is caught, the gazelle instantly goes limp (parasympathetic nervous system). The cheetah begins to play with the gazelle before going in for the kill. However, there is a hyena close by wanting a share of the gazelle. When the hyena comes into the picture, the cheetah is distracted and moves away from the hyena and the gazelle. The hyena begins to examine the frozen and non-responsive gazelle. Wanting to keep the gazelle for himself, the hyena momentarily moves away from the gazelle in order to chase the cheetah away. In this moment of distraction, the gazelle sees an opportunity for escape, it is up and sprinting off again, looking as if it suddenly came back to life (back into sympathetic nervous system response). When the gazelle was caught by the cheetah, its shutdown response kicked in — the gazelle froze. When it saw the opportunity to run away, its fight or flight kicked in, and it ran away to freedom. Polyvagal theory covers those three states—social engagement, fight or flight, or shutdown. Watch the video |

The Human ConnectionAs humans, we do the same thing as that gazelle when we perceive emotional or physical danger. We alternate between peaceful grazing (social engagement mode), fight or flight (sympathetic system- fight and flight) or shutdown (parasympathetic- shut down mode).

Our response is all in our perception of the event. Maybe someone was just playing a game when they jumped out to scare us, but we fainted. Whatever the reason, whether the incident was intentional or not, our body shifted into shutdown mode, we registered it as a trauma. our body shifted into shutdown mode. Or maybe the trauma event was really, life threatening, and our nervous system responded appropriately to the stimuli. No matter what the cause was, our brain believed what was happening was life threatening enough that it caused our body to go into fight, flight, or shutdown mode. If someone has been through such a traumatic event that their body tips into shutdown response, any event that reminds the person of that life-threatening occurrence can trigger them into disconnection or dissociation again. The opposite of the dorsal vagal system is the social engagement system. Therefore, what fixes shutdown mode is bringing someone into healthy social engagement, or proper attachment. When we understand why our body reacts the way it does, like a string of clues and some basic science about the brain, we can understand how to switch states. We can begin to move out of the fight or flight state, out of the shutdown mode, and back into the social engagement state. |

“The detection of a person as safe or dangerous triggers neurobiologically determined pro-social or defensive behaviors. Even though we may not always be aware of danger on a cognitive level, on a neurophysiological level, our body has already started a sequence of neural processes that would facilitate adaptive defense behaviors such as fight, flight or freeze. ”

Stephen W. Porges, The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-regulation

|

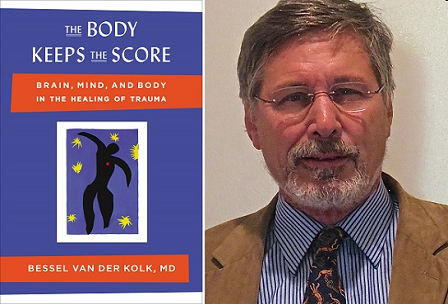

"The big issue for traumatized people is that they don't own themselves anymore. Any loud sound, anybody insulting them, hurting them, saying bad things, can hijack them away from themselves. And so what we have learned is that what makes you resilient to trauma is to own yourself fully." - Dr. Bessel van der Kolk

“Traumatized people chronically feel unsafe inside their bodies: The past is alive in the form of gnawing interior discomfort. Their bodies are constantly bombarded by visceral warning signs, and, in an attempt to control these processes, they often become expert at ignoring their gut feelings and in numbing awareness of what is played out inside. They learn to hide from their selves.” “As long as you keep secrets and suppress information, you are fundamentally at war with yourself…The critical issue is allowing yourself to know what you know. That takes an enormous amount of courage.” |

Befriending Your Body

"Trauma victims cannot recover until they become familiar with and befriend the sensations in their bodies. Being frightened means that you live in a body that is always on guard. Angry people live in angry bodies. The bodies of child-abuse victims are tense and defensive until they find a way to relax and feel safe. In order to change, people need to become aware of their sensations and the way that their bodies interact with the world around them. Physical self-awareness is the first step in releasing the tyranny of the past.

In my practice I begin the process by helping my patients to first notice and then describe the feelings in their bodies—not emotions such as anger or anxiety or fear but the physical sensations beneath the emotions: pressure, heat, muscular tension, tingling, caving in, feeling hollow, and so on. I also work on identifying the sensations associated with relaxation or pleasure. I help them become aware of their breath, their gestures and movements.

All too often, however, drugs such as Abilify, Zyprexa, and Seroquel, are prescribed instead of teaching people the skills to deal with such distressing physical reactions. Of course, medications only blunt sensations and do nothing to resolve them or transform them from toxic agents into allies.

The mind needs to be reeducated to feel physical sensations, and the body needs to be helped to tolerate and enjoy the comforts of touch. Individuals who lack emotional awareness are able, with practice, to connect their physical sensations to psychological events. Then they can slowly reconnect with themselves.”

Bessel A. van der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma

In my practice I begin the process by helping my patients to first notice and then describe the feelings in their bodies—not emotions such as anger or anxiety or fear but the physical sensations beneath the emotions: pressure, heat, muscular tension, tingling, caving in, feeling hollow, and so on. I also work on identifying the sensations associated with relaxation or pleasure. I help them become aware of their breath, their gestures and movements.

All too often, however, drugs such as Abilify, Zyprexa, and Seroquel, are prescribed instead of teaching people the skills to deal with such distressing physical reactions. Of course, medications only blunt sensations and do nothing to resolve them or transform them from toxic agents into allies.

The mind needs to be reeducated to feel physical sensations, and the body needs to be helped to tolerate and enjoy the comforts of touch. Individuals who lack emotional awareness are able, with practice, to connect their physical sensations to psychological events. Then they can slowly reconnect with themselves.”

Bessel A. van der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma